What is the “social brain” and how does it develop across childhood and adolescence? How has the significant increase in time spent on screen-based media by children in the last decade affected social development, and what can parents do about it? Children and Screens invited leading researchers in the fields of neuroscience and psychiatry to share the latest research on the social brain, review its development during key child maturation stages, and provide tips for parents and caregivers looking to support healthy social cognition in their children.

What Is The “Social Brain?”

The “social brain” represents a complex set of neural networks behind social cognition that center in areas of the brain optimized for social processes, allowing humans to partake in and understand all kinds of social behavior, from making inferences about others’ thoughts and behavior to understanding jokes and emotions.

How The Social Brain Develops Through Childhood

Early Childhood

In early childhood “our caretakers are the center of our social world,” says Moriah Thomason, PhD, Barakett Associate Professor and Director of Pediatric Neuroimaging, and Vice Chair for Research, Departments of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Population Health at New York University School of Medicine. “That social world also includes other figures, for example siblings, that support the way that our brain becomes a processing unit. That social context means everything to the way that the networks of the brain are formed.”

The development of key social functions begins in infancy. “The early infant understands joint attention, which refers to the ability to reference where somebody else is looking and look to that reference point. You’ll see little infants do this around nine months of age,” says Thomason. “Later, very young children learn turn-taking, a term that we use for conversational turns, where you take a pause and you look for a reaction from somebody else. These are fundamental, but it shows you that already the very young brain is learning how to operate within a social world.”

From infancy to preschool age, “some of the first social tasks would be emotion and behavior regulation. In other words, self-control – controlling one’s emotions and controlling one’s behavior,” says Georgene Troseth, PhD, Professor of Psychology, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University. “Another important aspect is understanding; identifying and understanding emotions, both your own emotions (when you’re happy, when you’re fearful, sad) and to be able to identify other people’s emotions. Empathy is another early social skill, as well as turn-taking, listening and sharing.”

Middle Childhood

As children age, the “connections in the brain are pruned over time, and we know that the environment has a profound effect on that. The brain is born with overabundant connections, and early experiences help the brain to know ‘this is an important connection for me to hold on to; this is one that’s a little bit unnecessary.’ We’re building brains that are efficient,” says Thomason.

Children in middle childhood begin attending school and experience their “first foray into long periods of learning in a social context that is outside of the home,” says Thomason. “We also begin to understand, consequences of our actions, we grapple with concepts like justice and fairness. We begin to understand empathy and altruism. We have a prefrontal cortex that is increasingly supporting goal-directed behaviors. And all of this in the context of being able to understand how to be persistent on tasks, and how to understand the consequences.”

Adolescence To Early Adulthood

What about adolescents? “Things get very interesting in adolescence,” says Thomason. “The job of the brain, from an evolutionary perspective, in adolescence is to support furthering us along that pathway to independence, where we’re able to go into the world and navigate without so much dependence on that family unit.” This journey to independence is reflected by how the brain starts to respond to social information. “We actually transition to being more reactive or more responsive in terms of brain activation to others outside of the home, instead of to our parents. We also see that children in this time become more activated in areas that are important for reward processing when they’re exposed to others. We are more rewarded by those signals and we’re less averse to potential risks,” says Thomason.

Prosocial: “Denoting or exhibiting behavior that benefits one or more other people, such as providing assistance to an older adult crossing the street.”

The social brain development in adolescence confers many benefits and advantages, says Eva Telzer, PhD, Co-Director, Winston National Center on Technology Use, Brain, and Psychological Development and Associate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at UNC Chapel Hill. Understanding other people’s mental states and being able to understand what other people are thinking and feeling, or having a “theory of mind”, is “essential for empathy and prosocial behaviors,” says Telzer, “but at the same time, heightened social cognition enhances adolescents’ concerns with what other people are thinking.” Once adolescents start understanding other people’s distinct thoughts and feelings, “they might become preoccupied with the notion that other people’s thoughts are focused on their own behaviors, or their appearance. And this might cause greater feelings of self-consciousness: a greater attunement and concern over peers, concern about peer evaluation and peer acceptance.”

The brain regions specialized for social processes continue to develop across adolescence and into the young adult years before stabilizing, says Telzer. “This protracted development in the social brain really demonstrates that areas of the brain that are involved in thinking about others and the mental states of others are still maturing across the adolescent period.”

Impacts Of Screen-based Media On Social Brain Development

How does the proliferation of screen-based technologies and media affect the development of these social neural networks in children? Researchers are seeing impacts across childhood.

Early Childhood

For young children, “the big issue here is what’s termed displacement: the idea that children need sufficient time with caring individuals who interact with them, who model social skills and help them regulate their emotions and their behavior. And so if, if a child is doing something else, they might not get the sufficient time to develop, to have those experiences, that will allow them to develop that,” says Troseth.

Recent research indicates that the frequent use of mobile devices as a calming mechanism for young children “may displace their opportunities for learning emotion-regulation strategies over time.”1 In doing so, “the child doesn’t have to struggle and develop their emotion regulation and their behavior regulation,” says Troseth.

Troseth notes that there is a notable positive use for social development of young children with screens – video chat. “Video chat allows that kind of sensitive responding, that back and forth. And we’re finding out that grandparents’ sensitivity to the baby, as in responding at the right moment with smiles and emotional expressions, is influencing infants’ emotions, and it is building the kinds of things that you could build face-to-face, with a supportive caregiver.” In line with these findings, the American Academy of Pediatrics exempts video chatting from their recommendations against screen time before 18-24 months.2

Adolescence

“In the span of just a generation, social media has dramatically changed the landscape of adolescent development, providing unprecedented opportunities for social interactions around the clock,” says Telzer. She notes that “this rise in social media use is happening at a critical developmental period when the brain is undergoing more development and reorganization, second only to that which we see during infancy.”

The social brain in adolescents is wired to seek social acceptance, crave social rewards, such as likes, and avoid social punishments, such as peer rejection, says Telzer, and adolescents using social media “may have the potential to be exacerbating or enhancing an already sensitive brain, further tuning adolescents to seek out more social rewards online.”

This innate receptiveness of sensitive adolescent brains to the powerful reward mechanisms of social media can help explain the strong draw of these platforms for this age group, says Telzer. Research has shown that when adolescents receive greater likes on social media posts and pictures “they show greater activation in regions of the brain implicated in the social brain network, as well as regions involving reward, learning, and motivation.”

Other recent research indicates that adolescents around the age of 12 years old who were habitually checking their social media accounts showed differences in how their brains are developing over the next three years3. For youth engaging in this repetitive behavior, “the brain is changing in a way that is becoming more and more and more sensitive to social feedback over time.”

“The Risk Years”

Teenage years are “the risk years” and teenage brains are “driven to take risks, seek peer admiration, and novelty” says Shimi Kang, MD, FRCPC, Clinical Associate Professor at The University of British Columbia and author of The Tech Solution. The teenage brain’s inclination for novelty and greater risk-taking can last until around age 25, and can sometimes manifest through online addiction and other online risk-taking behaviors. “That’s why teenagers love rollercoasters and scary movies,” says Kang, “and they’re also satisfying some of those desires online. So, when you look at a TikTok challenge, there’s some risk-taking in there. Maybe you’re doing something silly, you’re gaining admiration, you’re trying something new, it’s a novelty.”

These “risk years” last up until around the age of 25, and behavior during this period can also serve as the “seeds” of addiction, says Kang. “Whether it’s sugar in the diet, alcohol, drugs, gambling, or social media – whatever it might be, even perfectionism, these are the really critical years where you want to really be there shoulder to shoulder in their online world as well as their offline world.”

Tips For Parents And Caregivers For Screen Use And Social Development

Online Vs Offline Peer Experiences – It’s Just Different

Parents and caregivers should understand that online peer experiences differ markedly from offline peer experiences for adolescents and teens, says Telzer. “Social media now allows access to social information at any time it’s desired. It’s designed to hold users’ engagement and it maximizes social reward” with quantifiable social cues that “make these types of peer relationships very different from what they may look like in person.”

Social media also inverts a traditional understanding of “social time” by providing social experiences that are asynchronous (not necessarily happening in real time). In addition, all interactions may become “public and permanent” with possible consequences long after an interaction or post.

Conversation And Active Monitoring

Talk early, often and openly with your child – less than 35% of parents are talking to their children and adolescents about their online experiences, says Telzer. However, for adolescents, research supports parents and caregivers leaning into “active monitoring” of children’s media use. “Engaging in conversations and helping adolescents develop critical thinking regarding their social media use and having these discussions about the content of their social media rather than restricting the time that they’re spending online, can be very positive,” she says.

Kang stresses the need for repeated conversations rather than one-offs – “it has to be more than one conversation, it has to be repetitive, and it happens over time.”

Content, Context, Child

Instead of aiming for strict, blanket rules around screen time, Troseth advocates for consideration of the “3 C’s” of media use – content, context, and child4. “What’s on the screen (the content), what’s the context – is there a social engagement around it? Is it displacing something? Is it a time that the child should really be struggling on their own with regulating their behavior and emotions? And your own child, how old are they? What’s their temperament? And is there a disability, or some reason that a screen might be particularly valuable for that child?”

With these specific considerations in mind, you can better determine the specific needs and guidelines around screen time for your individual child.

Prioritize Tech-Free Night/Sleep Time

Charge devices outside of the bedroom in a common space, and consider a “curfew” on screens that is at least 1-2 hours before bedtime. Kang is unequivocal about the importance of limiting tech time at night. “When I’m asked for the one piece of advice to give to parents, it’s ‘no tech use after eight or nine pm,’” she says. “Cut it off completely, because it impacts the biological rhythm of sleep. The stress associated with that need to be connected at night prevents them from sleeping, as does receiving messages or waiting for likes or comments. All of these aspects of tech use at night are really disruptive for adolescent’s development and children’s development.”

A lack of consistent and good sleep “is associated with slower and different developmental trajectories in brain development, academic performance, car crashes, academic failures” and more, says Telzer. “And because technology use and social media use, especially at night, is related to sleep, we can make some pretty strong conclusions there about those links.”

Be Pro-Connection

Co-use with younger children and deliberative brainstorming with older children can help model and establish healthy uses of tech.

For younger children, co-engaging your young child with online content can help turn something passive into a more prosocial experience, says Troseth, who suggests asking questions about content a child is already interested in to engage and use vocabulary. “It’s a great opportunity to have a conversation, to ask your child, ‘What do you love about it? What’s fun?’” Research also indicates that video chat with family members is also a positive opportunity for social development for young children.

Encouraging adolescents to use their screen time in positive ways can help them achieve moderation and balance, says Telzer. This can include browsing more prosocial content rather than engaging in social comparison and envy, engaging in self-expression that is using more positive and accepting forms of affirmation (rather than expressing themselves in terms of concern for others), and using social media to connect and engage in more close relationships, rather than disconnecting and isolating themselves from their peers.

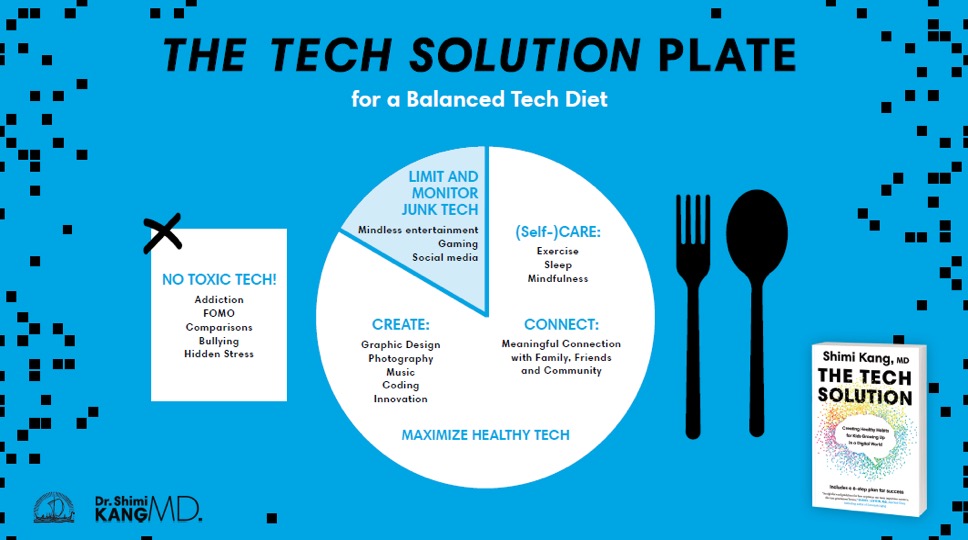

Establish A “Healthy Tech Diet”

“Just like there are toxic foods, things we want to avoid, like spoiled milk and aspartame, there’s certain tech we actually would be better off just avoiding”, says Kang, who advocates for a “Healthy Tech Diet.” Like junk food or sugar, toxic tech time won’t necessarily cause harm in the moment but an accumulation over time will have its effects.

What is “toxic tech?” Kang warns against the addictive nature of time spent with media that encourages regular dopamine response, such as mindless social media scrolling or passive gaming. She also notes that cortisol release through stress is a critical pitfall. And though many people of all ages often view their tech time as a stress release, “we have to understand tech has a lot of hidden stresses,” and tech time can turn into a cycle of managing stress with… more stress.

What is “healthy tech” in the “Healthy Tech Diet?” Kang says the solution to junk and stressful tech is tech use that enhances coping skills, social skills, and emotional skills, and “tech that releases endorphins through self-care, oxytocin through positive social connection, and serotonin, which we get from learning, from play, and from creativity.” Kang suggests wiring children early for healthy tech use, such as using apps for learning breathing and mindfulness techniques and play-based problem-solving. For older children, continuing to use tech for coping skills, self-care, connectivity, and trying new and different things is key, says Kang, who suggests relaxing nature-based screensavers or sounds before bed, as well as encouraging teens to create music playlists for three different purposes: relaxation/downtime, connection, and hype or positive music.

Pay Attention And Watch Your Own Tech Use

Parents themselves can often become distracted by technology in the presence of their children, a behavior known as “phubbing,” and some households may have a TV on in the background most of the day. Troseth cautions caregivers to pay attention to the social consequences of parental use of screens and background screens in the home environment, which can “actually lower many different important things: conversation, interaction, and children’s focus on their play – they get distracted.” While “no tech” is an unrealistic goal, Troseth urges parental recognition of the signs that their family tech environment is negatively affecting children, “whether they’re getting sufficient time with you, whether they’re developing in step with other children, assuming that they are neurotypical” and otherwise on par with developmental milestones.

Build In Tech Breaks To Family Life

Habit-stacking daily family time with tech-free time, such as family dinner time, can confer many benefits to children and families, says Kang. “One of the most robust findings in human development is when children eat dinner with the family, looking at and seeing each other, not only do we see better mental health, we see better academic performance as well. There’s a lot of daily habits that we can use to have a bit of that detox or fasting.”

It’s Not Too Late

Many parents worry that the “ship has sailed” when it comes to the impacts to the social brain of adolescents and young adults from problematic media use. Telzer says it’s actually the “perfect time” to intervene and help direct adolescents to more positive social and developmental trajectories. “The adolescent brain is in a state of flux and change and is very sensitive to its environment. This is the time to help direct adolescents to more positive online experiences or events, to help them engage in more real life social interactions. This time is when we can make those changes, and “undo” the potential things that might have started to occur in the context of negative online or technological experiences.”

Kang agrees that “it’s never too late. We humans have what’s called neuroplasticity…. the ability to learn and change our habits and behavior at any time.” While young people may resist changing habits around media, particularly if they are showing signs of addictive media use, Kang notes that the science and tools are available to move youth into positive action.

Notes

1 Radesky et al., 2022

2 Chassiakos et al., 2016

3 Maza et al., 2023

4 https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/kids-tech-q-a-with-lisa-guernsey/2011/12